The fifth largest economy in the euro zone seeks to leave political instability behind this Wednesday in its third legislative elections in five years. The Dutch go to the polls to choose the composition of the next Parliament. Around 13.4 million people are called to vote in one of the most uncertain elections in memory.

The abrupt withdrawal of Geert Wilders of the coalition led by the independent Dick Schoof motivated the electoral advance. Last June, the ultra leader launched an order to his partners asking to toughen asylum laws. He sent a list of unaffordable proposals that found no response.

The Cabinet formed by the People’s Party for Freedom and Democracy (VVD, liberal-conservative), the New Social Contract (NSC, Christian Democrat), the Peasant-Citizen Movement (BBB, agrarian populist) and the Party for Freedom (PVV, far-right) of Wilders then collapsed.

It will be impossible to reissue the same government formula, which took 223 days to materialize in a coalition agreement that Wilders blew up just eleven months later.

“The previous Cabinet also fell prematurely, again because of Wilders, so, in reality, the Netherlands has been characterized since 2021 by political instability that leaves little room for long-term policies or plans,” laments the political scientist. Roderik Rekker in conversation with this newspaper.

This Wednesday is also the early end of the Schoof era. The former spy chief, a gray leader with a social democratic past, will not go down in history as a great prime minister. His Government was burdened from the first moment by inaction.

“If there is one thing that everyone agrees on, even the parties that were part of it, it is that the Schoof Cabinet was a chaos, with constant disputes,” explains Rekker.

“The outgoing Government was made up of four parties, of which three had no previous experience,” he adds. Sarah de Langeprofessor of Political Science at the University of Leiden, in dialogue with EL ESPAÑOL. “Ministers, especially those from BBB and PVV, performed poorly, and many of the proposals were not viable because they did not conform to constitutional and rule of law principles.”

Schoof will remain in office until the formation of the next Government, a process that promises to last a few months.

The Prime Minister of the Netherlands, Dick Schoof.

Reuters

Paralysis

The House of Representatives in The Hague only has 150 seats, but no party can achieve a majority alone. The system is designed to articulate coalitions. It is necessary to agree. But the climate of polarization is not helpful. There is also a widespread belief that the need to reach consensus has plunged the Netherlands into paralysis.

Its politicians are more trained in the art of negotiation than in decision-making, which means that electoral tactics end up displacing deep reforms. This state of affairs sows the ground for populist speeches. So it’s no surprise that Wilders leads (almost) every poll.

The leader of the PVV obtained his best historical result in the November 2023 elections. His personal party went from 17 to 37 seats. The ultra leader hopes to repeat or surpass the feat, but it will be difficult for him. According to Ipsos, it is around 26 seats. It could cease to be the leading political force in the country.

Wilders, furthermore, was isolated after breaking up his second government coalition. It is perceived as an element of instability. An impression that does not seem to matter too much to his voters, but it does to the political parties. That is why it is unlikely that he will be part of the next Government. During the campaign, the main parliamentary leaders have made it clear that they rule out making an agreement with their PVV.

“There is no scenario in which the PVV could once again form part of the Government,” says Rekker. Anyway, as explained Stijn van Kesselprofessor of Comparative Politics at Queen Mary University of London, parties ranging from the centre-right to the right “have moved towards the PVV on immigration issues. So Wilders’s influence remains considerable.”

The desire to exclude him from governability does not respond to democratic hygiene, but to a mere electoral calculation.

“With Wilders out of the game, it is possible that former PVV voters will move towards other right-wing parties,” Van Kessel points out in this regard. “But there is still an important core of voters loyal to the PVV. So it remains unpredictable who will be the largest, although it is clear that we will once again have a fragmented Parliament.”

Wilders refuses to be pushed aside. “If the PVV turns out to be the biggest party on Wednesday, and you turn your back on us – that is, if you don’t even want to talk or govern with us – then democracy will be dead in the Netherlands,” he threatened last Saturday from the fishing town of Volendam.

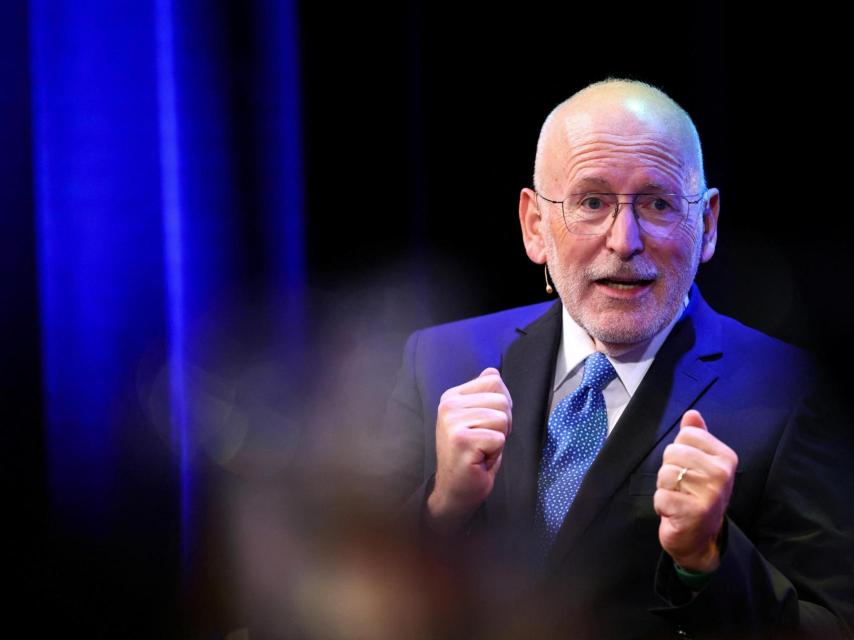

The leader of the GroenLinks-PvdA party, Frans Timmermans, during an interview at the University of Twente.

Reuters

Frente anti-Wilders

One of the underlying currents in these elections is the anti-Wilders vote, a vote that “is directed mainly towards left-wing parties,” says Van Kessel. That block is headed by Frans Timmermansthe leader of the coalition of social democrats and environmentalists, GroenLinks–PvdA, “who makes many references to Spain as an example country,” highlights Rekker, “especially in immigration matters.”

The platform of the former vice president of the European Commission is around 25 seats, according to the average of polls, but his figure generates some rejection in the right-wing bloc, the majority in Parliament.

“Timmermans is perceived, especially by far-right parties that act against the ‘left elites’, as the favorite opponent,” Van Kessel emphasizes. “In the past, Wilders always had his own preferred enemy to position himself against. The idea that Timmermans is not popular with the general public is frequently repeated in the media, so that narrative framework takes on a life of its own.”

“He is the target of conservative parties, who try to distance themselves from him,” adds Rekker along these lines.

This Monday, however, Wilders had to apologize. An unusual exercise for him. A Facebook page run by two PVV deputies shared images of Timmermans generated by artificial intelligence. In one of them, the social democratic leader appears handcuffed and escorted by the police.

“Inappropriate and unacceptable,” Wilders wrote on the social network X. “I distance myself from it. The site is offline. My apologies to colleague Timmermans.”

Bontenbal y Jetten, aspirantes a todo

Behind Timmermans figure Henri Bontenbal. The leader of the Christian Democratic Appeal (CDA) is another of the most popular candidates to replace Schoof as prime minister.

His party, which has championed the defense of the climate and the need to resolve the housing crisis, is hot on the heels of GroenLinks–PvdA in the polls, and in some cases even appears ahead.

In the final stretch of the campaign, however, Bontenbal was the target of criticism after his appearance on the public radio and television program Nieuwsuur. NOSwhere he showed little empathy with a homosexual student who lamented the lack of acceptance he received in his reformed school, a Protestant educational center. He himself recognized his mistake.

Bontenbal calls for establishing a cordon sanitaire for both Wilders’ PVV and the Forum for Democracy (FvD) founded by Thierry Baudettoday in low hours. Not so for JA21, a split from the FvD closer to the conservative right that leads Joost Eerdmans.

Rob Jetten He also has quite a few ballots to succeed Schoof. The former Minister of Climate and Energy in the fourth Government of Mark Rutte has worked the miracle of reviving the Democrats 66 (D66).

The socioliberal party exceeds fifteen seats in the most recent polls. Ipsos grants them no less than 24 seats in the Parliament of The Hague. A figure that would equal its best historical result.

Netherlands, Verian poll:

Seat projection national parliament

PVV-PfE: 29 (-5)

GL/PVDA-G/EFA|S&D:

D66-RE: 24 (+8)

CDA-EPP: 19 (-4)

VVD-RE: 16 (+1)

JA21~ECR: 8 (-4)

FvD-ESN: 6 (+2)

SP-LEFT: 5 (+1)

BBB-EPP: 3 (+1)

THINK-*: 3

SGP-ECR: 3

CU-EPP: 3 (+1)

PvdD-LEFT: 2 (-1)… pic.twitter.com/VtT6K7twHe— Europe Elects (@EuropeElects) October 28, 2025

In September, the national headquarters of D66 was attacked by far-right activists. Jetten handled the incident well. He aroused sympathy in public opinion. So many, that the party reached its highest number of members since 1966.

“D66 has moved a little to the right socioculturally and is following a catch-all strategy,” explains Van Kessel, who considers that Jetten “seems to have adopted Rutte’s style. For this reason, the party now plays a much less marked role as a counterweight to Wilders than in the past.”

Another of the proper names of these elections is that of Dilan Yesilgoz. It seemed that Rutte’s successor at the head of the VVD was going to lead her party—dominating the national political scene in the last two decades—towards the worst result in its history, but she emerged reinforced by the absence of Wilders in several debates, in which she was able to present herself as a reasonable alternative to the extreme right.

The former Minister of Justice and Security, the main architect of the anti-Timmermans wall, defined Wilders as “a single man with a Twitter account.” It has around 15 seats, according to the polls.

Frans Timmermans, Dilan Yesilgöz, Rob Jetten, Henri Bontenbal, Joost Eerdmans and Jimmy Dijk join the debate.

Reuters

No trace of the international scene

The campaign has revolved around the issue of housing, the rising cost of living and, above all, immigration, the cornerstone of Wilders’ strategy to maintain his influence.

“In many debates, the issues of immigration and housing shortages were linked together, especially by right-wing politicians,” explains De Lange. “They attribute the lack of social housing to asylum seekers with residency status, as well as the pressure exerted by expatriates and migrant workers on the private housing rental and purchase market.”

The international scene, defense policy or the rule of law have been relegated to the background.

“Geopolitical issues play a surprisingly small role,” laments Van Kessel. “Normally they are not very present in electoral campaigns, but on this occasion it is especially striking given the global situation.”

“There is hardly any talk about geopolitical issues, except for the debate on how long we should maintain the increase in defense spending,” says Rekker, who acknowledges that “there is also not much talk about the rule of law, although some parties do point out that certain proposals—especially those of Wilders—erode it.”