For some time now, infrastructures have proven decisive when it comes to examining the processes of capitalist exploitation about bodies, territories and habitats. The very idea of “infrastructure” is ambivalent, since it can serve both to subjugate and to offer maintenance, repair and care. This makes many artists feel attracted to them today.

In her first individual exhibition in Spain, the Lebanese artist Marwa Arsanios (Washington DC, 1978) addresses pressing problems such as extractivism and expropriationas well as the resistances with which to face these processes. Her practice is that of the research artist and activist who summons some of the “turns” in art in recent decades: the documentary, anthropological and social turns that make art a laboratory of the real.

This exhibition brings together the series of five audiovisuals entitled Who is Afraid of Ideology? (Who’s Afraid of Ideology?) that the artist has been making from 2017 to the present. From the outset, the title already shows a clear political intention; If ideology remains dissolved in the order of appearances and in everyday life, if it is not visible, then who can be scared?

The role of the artist then consists of reveal these opaque and often imperceptible processes. Its main theme is the importance of land and the colonial mentality of ownership. Its response is the distribution and usufruct of the land by different communities that supply themselves with resources and services for group life.

A militarized feminist group in Iraqi Kurdistan; the masha’a or communal lands in Lebanon; or a collective of women in the coffee-producing region of Tolima (Colombia) that resists the monoculture of multinationals thanks to the value of seeds in indigenous cultures.

Marwa Arsanios: Still from ‘Right of Passage’, 2025. Photo: Marwa Arsanios

Arsanios investigates these cases that challenge the traditional notion of property and participates from within in a shared search for permaculture and agricultural redistribution.

Los links between colonialism, violence and landscape segmentation are clear. In a way, the exhibition consists of the mental exercise of transferring what we see in the videos also to other nearby situations, since capitalist speculation has long used more invasive and coercive ways of occupying land. In response, the artist proposes utensils at the service of the community.

In all these audiovisuals Arsanios slightly avoids the author’s documentary and the essay film, cautious regarding the extractivist component and moral superiority of those who stand behind the camera in the documentary genre. There is something of a manifesto, of guerrilla cinema and Truth truth.

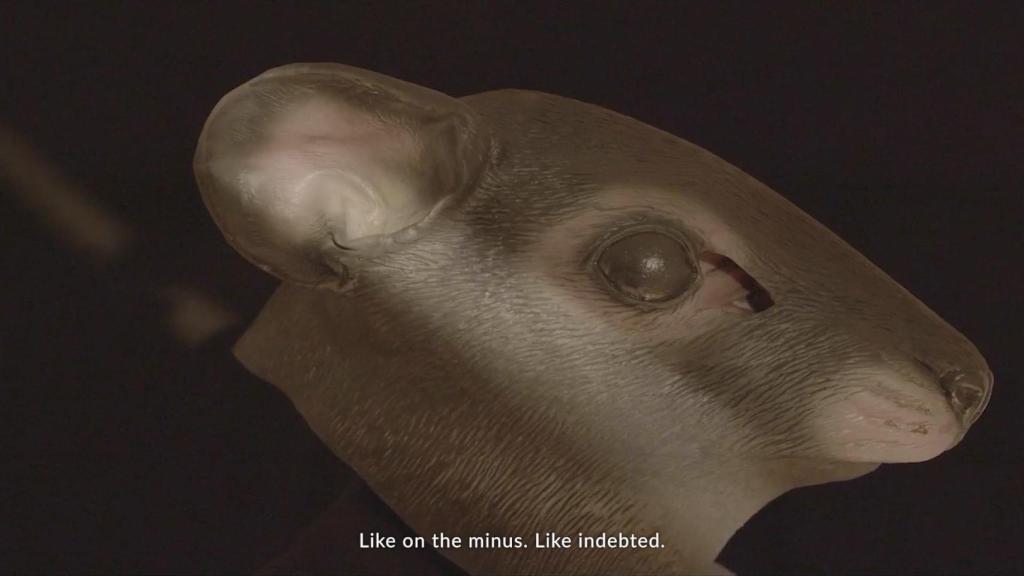

However, in the fifth and last of the videos in the series titled Right of Passage (2025), and which deals with the right of passage of animals in the countryside, a more fictional and fabulatory desire is perceived. It is as if the current global and humanitarian crisis required an extra bit of imagination.

Marwa Arsanios: Photogram from ‘Right of Passage’, 2025. Photo: Marwa Arsanios

In the video humans have animalized and become micenegotiating their routes through fertile lands (the Bekaa Valley in Lebanon) or cobblestone streets (Berlin). This is a production made specifically for this exhibition in collaboration with the Fundació Joan Miró of Barcelona, and is presented in parallel at its Espai 13, within the Loop Festival.

As an extension to these videos there are textiles, drawings and maps of diluted authorship carried out with the women of the communities.

Marwa Arsanios rarely mentions the word “art” but considers cultural institutions as infrastructures whose micro-resources can help these communities in a political and economic way.

It thus points out its interconnected nature in globalization. Theory and praxis. The nearly three hours of looped audiovisual footage traces cognitive maps and they invite a viewer who may feel overwhelmed by the viewing time. However, the breadth and relaxation of the exhibition format to house the content works as an antidote to the immediacy of current consumption.

The good thing about this type of artistic practices is that there is always a text, a conference or a pedagogical workshop connected to the social problems addressed. Participation and debate remain open.

All in all, this exhibition shows the tensions and gaps between discourse, community activism and aesthetic formalization, highlighting at the same time that contemporary art or, rather, its institutions, can also serve as sounding board of the world’s critical consciousnessfrom the genocide in Gaza to the rise of neo-fascism.